- Home

- Leslie Bennetts

Last Girl Before Freeway

Last Girl Before Freeway Read online

Contents

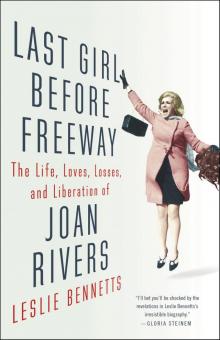

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One: Nobody Ever Wanted It More: “But She Has No Talent!”

Chapter Two: Dying Is Easy. Comedy Is Hard.

Chapter Three: Dicks and Balls: Breaking Into the Boys’ Club

Chapter Four: Stardom and Wifedom: Happily Ever After?

Chapter Five: Westward Ho: California Dreamin’

Chapter Six: The First Lady of Comedy: Nothing Is Sacred

Chapter Seven: Victim as Enforcer: Terrorizing Women into Submission

Chapter Eight: The Temptation of Joan: Poisoned Apple

Chapter Nine: A Thankless Child: “How Sharper than a Serpent’s Tooth”

Chapter Ten: Debacle: The Death of a Show, a Marriage—and a Husband

Chapter Eleven: Recovery: The Long Road Back

Chapter Twelve: Reinventing a Career: “I Can Rise Again!”

Chapter Thirteen: Art and Commerce: All in a Day’s Work

Chapter Fourteen: Home Sweet Versailles: Marie Antoinette Meets Auntie Mame

Chapter Fifteen: High Society: Putting On the Ritz

Chapter Sixteen: But Is It Good for the Jews? Sex, Politics, and Religion

Chapter Seventeen: Men Are Stupid: Beauty and Betrayal

Chapter Eighteen: Back to the Top: Fighting Like “a Rabid Pit Bull”

Chapter Nineteen: Fashion Forward: Triumph of the Mean Girls

Chapter Twenty: Daughter Dearest: How to Succeed in Show Business

Chapter Twenty-One: The Time of Her Life: Fame, Friends, and Fun

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Final Mountain: Gathering Shadows

Chapter Twenty-Three: Grand Finale: Sudden Exit, Pursued by Bear

Chapter Twenty-Four: Legacy: Laughter and Liberation

Epilogue: Updates from the Afterlife: “You Were Fat, You Bitch!”

Photos

Acknowledgments

Note on Sources

About the Author

Also by Leslie Bennetts

Newsletters

Copyright

This book is dedicated to everyone who has lost love or work or money or success or youth or beauty or hope: may Joan’s indomitable spirit encourage you in your bleakest hours, inspire you to triumph over any odds, and remind you to keep your sense of humor along the way—as it has done for me.

Prologue

She sat on the bed, the gun in her lap. Everything seemed hopeless. “What’s the point?” she thought. She couldn’t think of one.

Only a few months earlier, Joan Rivers had everything she ever wanted: fame and fortune, the job of her dreams, a loyal husband, a loving child, a lavish estate—and a future that beckoned with enticing possibilities. After years of struggle, she had not only succeeded as a comedienne but had made history as television’s first and only female late-night talk show host.

And now she’d lost it all. The first lady of comedy was fired from her job and publicly humiliated. Her husband—unable to bear his own failure as her manager and producer—killed himself. Their daughter blamed her mother for his death.

Reeling with grief and rage, Rivers then discovered she was broke. She had earned millions of dollars and lived a life of baroque luxury, but her husband had squandered her wealth on bad investments. She was $37 million in debt, and her opportunities for making more money had vanished.

At the Bel Air mansion where five telephone lines once buzzed relentlessly, the phone never rang. Nobody wanted to hire her as an entertainer. Suicide wasn’t funny, and her husband’s tragic death turned her into a professional pariah. Even her social life evaporated. No one invited her to anything.

As her fifty-fifth birthday approached, she couldn’t see any reason to keep on living. It was hard enough for young women to succeed in show business, but for an aging has-been, resurrecting a ruined career seemed impossible. Her home once sheltered a happy family; now the rooms echoed with silence. In her fancy peach-colored bedroom, she was alone.

“This is stupid,” she thought.

And then her Yorkshire terrier jumped onto her lap and sat on the gun. Rivers knew her way around firearms; she often packed a pistol, and she felt no hesitation about using it. Once, when an assistant accidentally surprised her in the middle of the night, Rivers thought she was an intruder and accosted her with trigger cocked. “Your time’s up,” she said calmly, ready to fire.

Maybe that was the answer now: one moment and the act would be done.

But then a terrible thought occurred to her: If she killed herself, what would happen to Spike? The diminutive Yorkie was very cute, but he was also mean and cantankerous. He didn’t like anybody but his mistress, and he was ridiculously spoiled; his favorite food was a rare roast beef sandwich, no mayo or mustard. Joan’s daughter referred to him as “a tall rat.”

Without Joan, who would protect and pamper the tiny dog she loved so much?

“Nobody will take care of him!” she realized, aghast.

As she sat on her bed, staring down at the gun, no oddsmaker would have bet on Rivers’s future. In the history of show business, no middle-aged woman had ever done anything remotely comparable to what she was about to do.

But Rivers didn’t shoot herself, and she refused to give up and slink into oblivion. Written off as a lost cause, she started over, invented new opportunities for herself, and went on to achieve the impossible. Working with maniacal fervor through her sixties and seventies and into her eighties, she re-created herself as a cultural icon, a vastly influential trailblazer, and a business powerhouse who built a billion-dollar company.

In the process, she rewrote her entire life story. Raised to believe in the classic fairy tale of happily ever after, she had been desperate to find the requisite husband. When she finally got married at thirty-two, she was overjoyed to have a loyal helpmate who looked like the black-suited groom on a wedding cake—and even more thrilled when baby made three.

In her thirties and forties, Rivers achieved her very own, uniquely modern version of the American dream, a forward-looking combination of classic male goals and conventional female aspirations. Like a successful man, she earned wealth and fame, but she also had a happy family—the Good Housekeeping seal of approval for any woman, no matter how accomplished.

Together, Rivers and her husband created a marital mythology that enshrined her as the star but credited him as the essential power behind the throne. But as the years went on, appearance diverged from reality—at first by a little, and then, terrifyingly, by a lot. Unable to keep up with his voraciously ambitious wife, the man in charge became increasingly depressed about his own lack of success. Instead of elevating her to the heights she craved, Mr. Right ended up playing the pivotal role in taking her down.

When she had to start again in midlife and go it alone, reality forced her to embrace a very different narrative. Her steady climb to the top had turned into a dizzying roller-coaster ride that ricocheted between spectacular triumphs and soul-crushing failures—a Dickensian saga of alternating extremes that included deep loves and tragic losses, stinging betrayals and enduring devotion, agonizing rejections and the adulation of millions, economic terror and riches beyond the wildest imaginings of all but the rarefied few.

None of it was what she expected. She grew up chubby and plain, with drab hair and thunder thighs and a horsey face that remained resolutely unpretty even after the requisite nose job. Fiercely jealous of Elizabeth Taylor, only a year older but a movie star even as a child, Rivers never got over her anger that she herself wasn’t beautiful.

But that seeming handicap proved far less important than she assumed. Throughout her life, Rivers believed tha

t beauty was the key to women’s happiness and success—and yet talent and ambition gave her rewards that far exceeded anything earned by the pretty girls she envied so bitterly.

She thought she needed a man to prop her up—but when she finally took charge of her own life, she became much more capable than the men she depended on. Convinced that a woman’s worth is measured by the intensity of men’s desire, she saw aging as the ultimate enemy—and yet she achieved her greatest renown long after passing the sell-by date society decrees to be the expiration of female sexual viability.

In her later years, Rivers claimed that Spike saved her life when he sat on her gun that day, but in truth her fate was preordained by the fanatical determination she always recognized as the core of her identity. “Even in my darkest moments, I knew instinctively that my unyielding drive was my most important asset,” she wrote.

That drive inspired her philosophy of life, which was as ferocious as it was uncompromising: “Never stop believing. Never give up. Never quit. Never!”

And she never did. After her life fell apart, it took her years to dig her way out of the wreckage. The process was hard and humbling, but it ultimately produced an outcome that no one, not even Joan herself, could have foreseen.

When she died at eighty-one, she was, improbably and amazingly, at the height of her fame—not only as a comic who battled her way back from oblivion, but as an insatiable overachiever who had fought her way into a dozen other fields as well.

After a sixty-year career, she was still doing stand-up comedy every week of her life, but she had also been an Emmy Award–winning talk show host; a radio host; a reality star online and on TV; the best-selling author of memoirs, fiction, and self-help books; a playwright and a screenwriter; a film star and a Tony-nominated actress on Broadway; a Hollywood movie director; a Grammy Award–winning recording artist; a CEO and designer whose company sold more than a billion dollars’ worth of jewelry and clothing on QVC; and a philanthropist who commenced her enduring support of AIDS patients at a frightening time when that commitment was a rare act of public bravery.

As a snarky fashion arbiter on the red carpet, Rivers played a key role in creating a multibillion-dollar industry that employed countless designers and stylists and hair and makeup artists and publicists and photographers and all the other minions of the voracious media that now feed off an endless round of celebrity galas and awards ceremonies, spawning a perpetual ratings bonanza of televised critiques.

All that frenetic activity made Rivers an icon to an enormous and wildly diverse audience. In her later years, her fans ranged from the little old Jewish ladies who were her actual contemporaries to the Middle American housewives who bought her rhinestoned bumblebee pins on QVC to the millennials of every race, religion, background, gender identity, and sexual orientation who followed her insulting, obscene commentary on Fashion Police.

Rivers never set out to be a revolutionary, but the things she said—as shocking as the toads jumping out of the nasty daughter’s mouth in the French folktale—had long since made her into one. When she started out in stand-up comedy, women simply didn’t do most of the things she ended up doing—let alone talk about them. But if polite society said it was taboo, Rivers couldn’t resist making fun of it.

Appalled by the hypocrisy of the prevailing social mores, she mocked the double standards that judged men by different criteria than women. If she was fixated on finding a husband, she was also merciless in lampooning the relentless pressure on women to land a man.

When Rivers made it onto The Jack Paar Show, she explained, “I’m from a little town called Larchmont, where if you’re not married, and you’re a girl, and you’re over twenty-one, you’re better off dead.”

Being Jewish only exacerbated the problem. On The Tonight Show, Johnny Carson asked her when Jewish parents start to harangue a daughter about her marital prospects.

“When she’s eleven,” Rivers replied.

Men had a lot more latitude. “Jews and Italians get very nervous if a daughter hits puberty and there’s no ring on her finger,” she observed. “A son can be ninety-five.”

A woman’s worth was measured by her youth and desirability, but men need offer little more than a pulse. “A girl, you’re thirty years old, you’re not married—you’re an old maid,” Rivers said. “A man, he’s ninety years old, he’s not married—he’s a catch.”

When her parents moved to the suburbs in the 1950s, the talk of Larchmont was the arrival of the New England Thruway, which bisected the town. As one of her signature comedic bits, Rivers conjured a vivid image to convey the endless humiliations her mother inflicted on the spinster daughter nobody seemed to want.

“I’m the last single girl in Larchmont,” Rivers said. “My mother is desperate. She has a sign up: ‘Last Girl Before Freeway.’”

Her mother expected Joan to do what she herself had done: get married, have children, and become a housewife obsessed with domestic perfection. And yet Joan’s mother was miserable; her husband didn’t earn enough money for the family to live the way she wanted, and their homelife was riven with bitter fights that forever scarred their children. Growing up in an explosive atmosphere of recriminations and regret, Joan vowed that she would never depend on a husband to support her.

What Joan wanted was fame—but achieving glory seemed even more remote than finding a nice Jewish husband. Ever since she played a pretty kitty in a preschool play, she had planned to be an actress, but she wasn’t pretty, and no one thought she had any talent. After graduating from Barnard, she was rejected by all the casting agencies, even when she crept in through the door on her hands and knees and crawled all the way to the receptionist’s desk to reach up from the floor and offer a rose with her white-gloved hand.

But finally one secretary laughed and said she was funny and maybe she should try comedy. When Joan started begging for the chance to do stand-up in Greenwich Village clubs, nobody thought she was any good at that either.

Behind their hard-won facade of middle-class gentility, her parents were frantic with worry. They couldn’t understand why Joan refused to settle for a normal life. Her conviction that she was destined for stardom seemed delusional, and they were doubly mortified when she performed at their beach club and bombed so badly they had to sneak out through the kitchen door rather than face their friends. Whatever “it” was, the universal consensus was that Joan Alexandra Molinsky didn’t have it.

Hurt and angry at their lack of faith in her dreams, Joan was undeterred. When an agent named Rivers told her that Molinsky wasn’t an acceptable name for a performer, she became Joan Rivers on the spot. Bemoaning her failures in coffeehouses and comedy clubs, she portrayed herself as a wallflower who was perennially rebuffed by men. Even in the grubbiest dives, she was booed off the stage and fired before the second show.

But slowly, Rivers learned how to handle an audience, a challenge that demanded the ferocious control of a lion tamer. If audiences were tough, her peers were worse. Comedy was a man’s world, and the men wouldn’t let her in.

So she refused to take no for an answer. Bulldozing through previously impenetrable barriers as if they were made of toothpicks, she crashed her way into innumerable clubs run by hostile men who didn’t want her. If they didn’t consider her pretty enough to seduce, she taunted them with her relish for defying their judgments. Girls were supposed to be virgins until they married, but Rivers closed her show with a startling come-on: “I’m Joan Rivers, and I put out.”

If women weren’t allowed to share their experiences, she forced people to hear about them anyway. When she was eight months pregnant with her daughter, Ed Sullivan forbade her even to mention pregnancy on the air. Women were supposed to remain pristine on their pedestals, impersonating sanitized mannequins unsullied by corporeal reality. Rivers shocked her audiences by talking about what it feels like when a woman visits the gynecologist: “An hour before you come in, the doctor puts his hand in the refrigerator.”

&nb

sp; Audiences gasped, but she was just getting started; by the time she was a senior citizen, she was regaling people with jokes about the effect of age on female genitalia. “Did you know vaginas drop? One morning I look down and say, ‘Why am I wearing a bunny slipper? And it’s gray!’”

By then she was an international icon whose extraordinary career had been forged from an attention-grabbing hybrid of traditional female concerns and bold new transgressions. Pathologically afraid of gaining weight, she starved herself into an acceptable degree of emaciation; for decades, she ate only Altoids when she went out to dinner with friends. But she also became a ruthless enforcer of such strictures. Lashing out at women who let themselves go, she made headlines for lambasting her childhood nemesis.

“Elizabeth Taylor’s so fat, she puts mayonnaise on aspirin.”

“Elizabeth Taylor pierced her ears and gravy ran out.”

“Mosquitoes see Elizabeth Taylor and scream, ‘Buffet!’”

Until the end of her life, Rivers savaged other women for not conforming to the dictates of popular fashion, and her cruelty made some listeners recoil. As a cultural assassin, she even kept up with the times; her targets evolved from Elizabeth Taylor to Lena Dunham, but the rage never left her. And yet she was equally fearless about violating the social taboos that had long kept women in a Victorian stranglehold.

In doing so, she helped to shatter those taboos—but even as she did so, she continued to personify the contradictions that define women’s lives. Until the week she died, Rivers performed outrageous comedy routines poking fun at the foolishness of men—but her entire life was shaped by her grief and anger at the male values that deemed her inadequate, no matter how hard she worked to live up to them.

She mocked the sexist and ageist attitudes that hold women back, but she remained hostage to the fears that made her into a virtual poster girl for grotesque excesses of plastic surgery. Mutilating her entire body with surgical interventions, she plumped up her sagging face with injectable fillers until she was unrecognizable as the plain young woman who had been catapulted to celebrity by a single star turn on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

Last Girl Before Freeway

Last Girl Before Freeway